Japan’s Shrinking Population Isn’t a Win for Nature—Here’s Why

The Environmental Impact of Depopulation: A Global Perspective

Since 1970, the world has witnessed a staggering loss of 73% of global wildlife. During this same period, the global population has doubled to reach an estimated 8 billion people today. Scientific research indicates that this rapid population growth is not merely coincidental but is directly contributing to a catastrophic decline in biodiversity.

However, a significant shift in human demographics is on the horizon. According to United Nations projections, by 2050, populations in approximately 85 countries are expected to begin shrinking, particularly in Europe and Asia. By the end of the century, global population decline may become the new norm.

Some experts believe this demographic transition could be beneficial for the environment. Japan was the first Asian country to experience depopulation, starting around 2010. This trend has since spread to South Korea, China, and Taiwan. In southern Europe, Italy led the way in 2014, followed by Spain, Portugal, and others. These nations have been termed "depopulation vanguard countries," offering valuable insights into potential future scenarios across their regions.

Given the hypothesis that depopulation might lead to environmental restoration, researchers Yang Li and Taku Fujita collaborated to explore whether Japan is experiencing what's been termed a biodiversity "depopulation dividend."

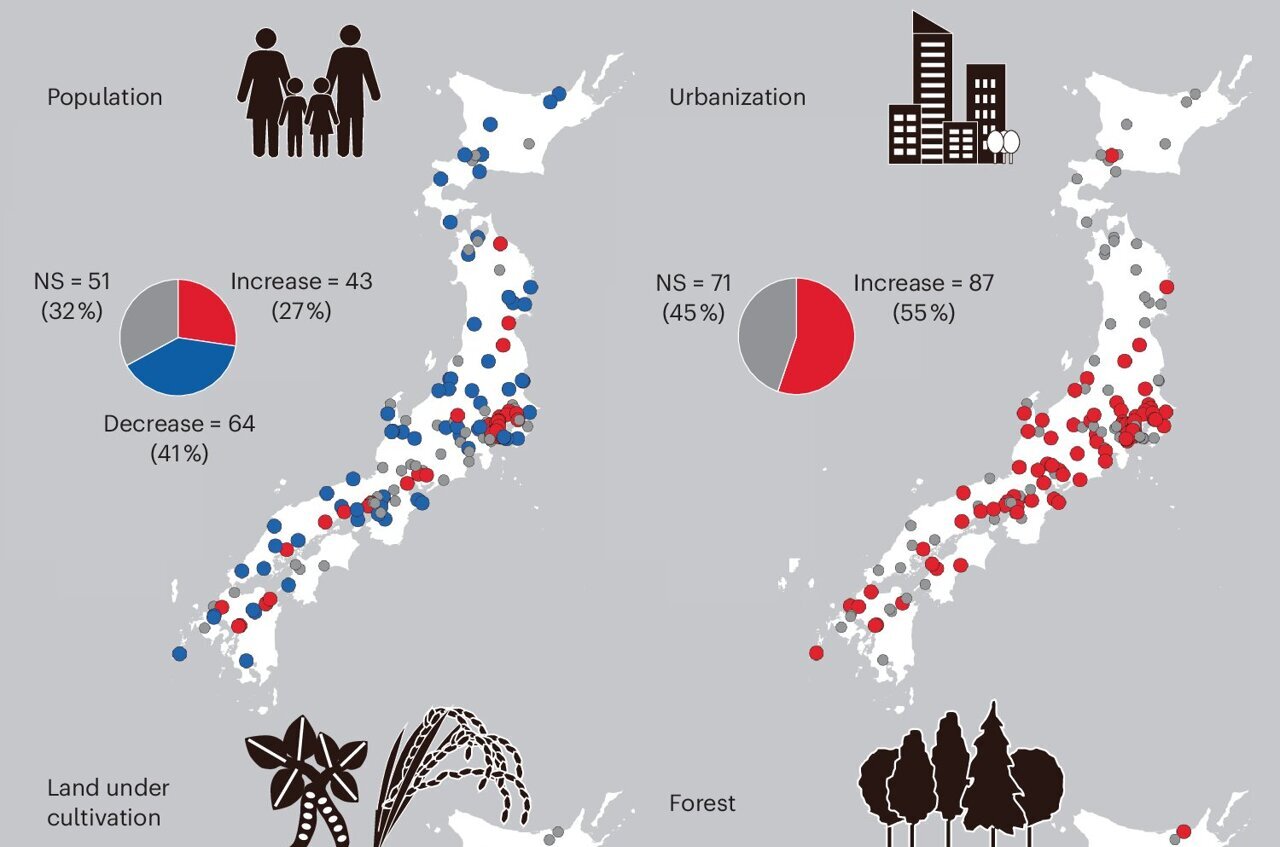

Their investigation utilized data from Japan's Monitoring Sites 1,000 project, which has been collecting biodiversity information since 2003 through the efforts of hundreds of citizen scientists. The study analyzed 1.5 million species observations from 158 sites located in wooded, agricultural, and peri-urban areas. Researchers compared these findings against local population changes, land use shifts, and surface temperature variations over periods ranging from five to 20 years.

Published in Nature Sustainability, the study encompassed birds, butterflies, fireflies, frogs, and 2,922 native and non-native plants. These landscapes have experienced some of the most pronounced depopulation trends since the 1990s.

Contrary to expectations, biodiversity continued to decline across most studied areas regardless of population trends. Only in regions with stable populations did biodiversity remain relatively constant. However, these areas face aging demographics that will soon result in further population declines, aligning them with other regions already suffering biodiversity losses.

Japan's gradual depopulation differs starkly from abrupt evacuations like Chernobyl, where sudden abandonment led to dramatic wildlife resurgence. Instead, Japan experiences a complex mosaic of land-use changes within still-operational communities.

While much farmland remains cultivated, some plots fall into disuse or are converted to urban development or intensive agriculture. This fragmentation prevents widespread natural succession or afforestation, processes that typically enrich biodiversity.

In these regions, humans play a crucial role in maintaining ecosystem sustainability. Traditional farming practices—such as rice field flooding, orchard management, and coppicing—are vital for sustaining diverse habitats.

Interestingly, while some species thrive under these conditions, many are non-native, posing challenges like invasive grasses overtaking wetlands. Additional complications arise from vacant buildings, underused infrastructure, and socio-legal issues such as inheritance laws, land taxes, administrative limitations, and high demolition costs.

The proliferation of akiya (abandoned houses), now comprising nearly 15% of Japan's housing stock, continues alongside relentless new construction. In 2024 alone, over 790,000 new dwellings were built, driven by shifting population distributions and household dynamics. Accompanying developments like roads, shopping centers, sports facilities, parking lots, and convenience stores continue to encroach upon wildlife habitats despite overall population decline.

Addressing these challenges requires proactive management strategies. Current rewilding projects in Japan are limited. Local authorities could be empowered to convert unused land into community-managed conservancies, fostering localized stewardship.

Globally, nature depletion poses systemic risks to economic stability. Ecological threats such as declining fish stocks and deforestation demand greater accountability from both governments and corporations. Rather than investing in more infrastructure for a dwindling populace, Japanese companies might instead focus on cultivating local natural forests for carbon credits.

Depopulation emerges as a defining megatrend of the 21st century. If managed effectively, it holds potential to alleviate pressing environmental concerns—from resource consumption to emissions reduction and conservation efforts—but realizing these benefits necessitates deliberate action.

Post a Comment for "Japan’s Shrinking Population Isn’t a Win for Nature—Here’s Why"

Post a Comment