A Man's 210-Sided Wheel Experiment Goes Wrong

The Unconventional History of the Polygonal Train Wheel

For most of history, trains have relied on the friction between steel wheels and rails to move forward. This process, known as adhesion traction, has been a cornerstone of rail transportation. However, this metal-on-metal contact can only provide so much grip. In the 1880s, one man believed he could change that.

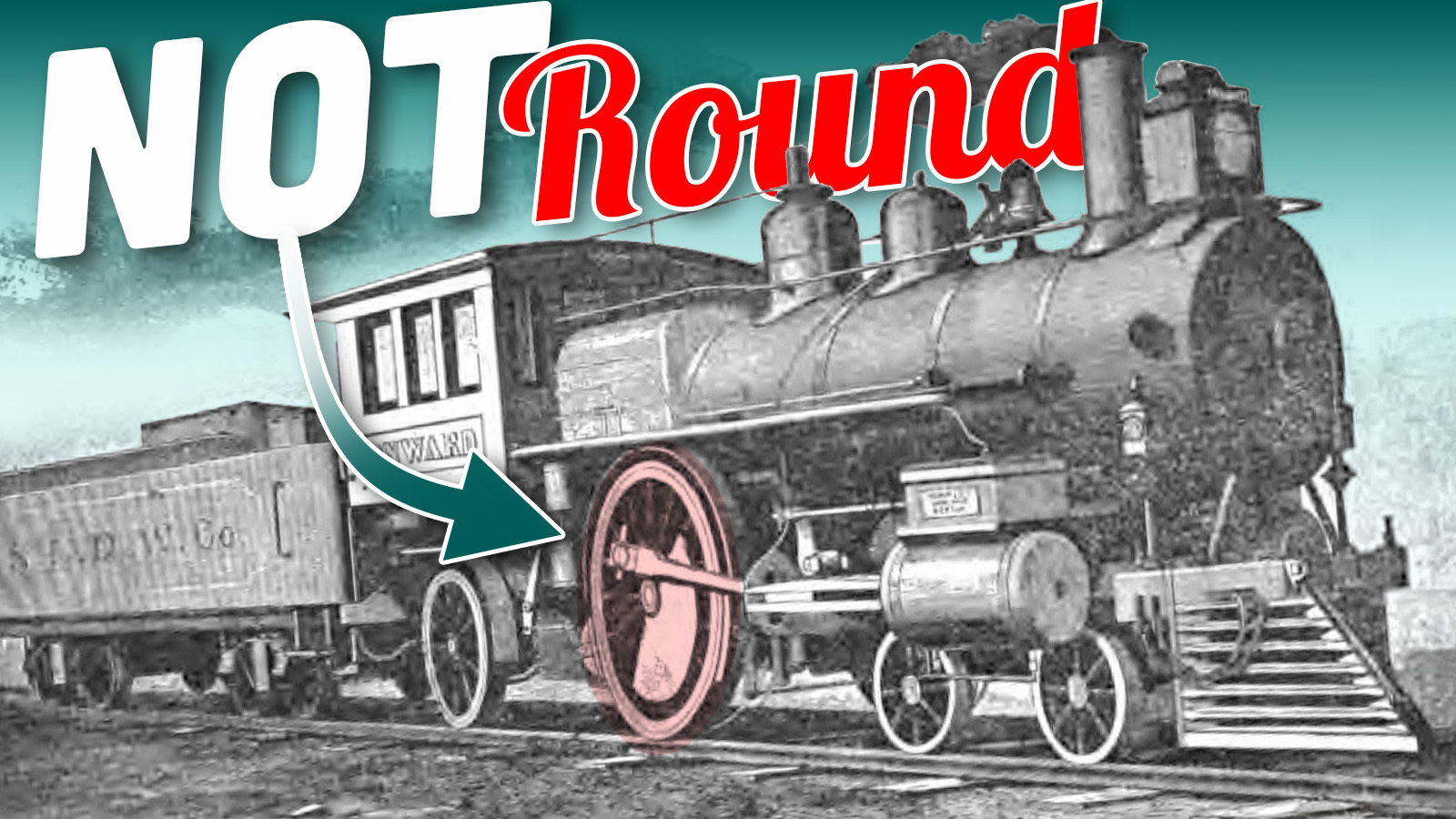

Charles E. Swinerton sought to revolutionize train design by replacing traditional round wheels with polygonal ones. His idea was simple: if the small contact patch of a round wheel limited traction, then making wheels with larger, flat surfaces would improve performance. Swinerton’s concept led to the creation of the locomotive called Onward, which featured wheels with 210 sides. This design, while innovative, ultimately failed to gain traction in the railroad industry.

A Unique Approach to Locomotive Design

Swinerton was based in New York and had a company in Maine called the Swinerton Locomotive Driving Wheel Company. The company worked with the Hinkley Locomotive Works in Boston to build the Onward in 1887. The locomotive used an older 4-2-2 wheel arrangement, which was considered outdated due to its limited adhesion. Some believe Swinerton intentionally chose this design to showcase how his polygonal wheels could outperform traditional ones.

The key innovation was the polygonal wheels. Each wheel had 210 sides, with each facet measuring about one inch long. According to Scientific American, these wheels were designed to increase traction significantly. The locomotive was tested on the Boston and Maine Railroad, where it successfully pulled the Portland express for six months.

Testing and Performance

The Onward underwent rigorous testing, including hauling coal from Boston to Lowell. It demonstrated impressive tractive power, even pulling more cars than traditional engines. Tests also showed that the polygonal wheels improved traction, especially on steep grades. Despite this, the wheels did not cause excessive vibrations or wear, and they ran quietly, similar to regular wheels.

However, there were challenges. The brake pads of the time were designed for smooth, curved wheels and struggled to function efficiently on polygonal surfaces. Additionally, while Swinerton claimed the wheels could be made cheaply, they were still more expensive than standard wheels. Railroads saw little benefit in adopting such a complex design.

Attempts to Revive the Idea

After the Onward failed to gain widespread acceptance, Swinerton tried to market his design to streetcar companies. In 1892, reports suggested that the Lobdell Wheel Co. was experimenting with cast-iron chilled wheels based on his design. By 1895, the Swinerton company had shifted focus to electric railways, claiming their wheels offered better traction and control.

Despite some initial interest, the technology never caught on. The Onward was eventually converted back to round wheels and sold to another railroad. It was later rebuilt into a more conventional design and scrapped in 1905.

Legacy of the Polygonal Wheel

Today, no manufacturers produce polygonal train wheels. However, the phenomenon of round wheels wearing into a polygonal shape is still a concern. This wear can lead to vibrations, cracks, and other issues.

Swinerton’s invention, while technically a breakthrough, failed to convince railroads of its practical value. His story highlights the challenges of introducing new technologies, even when they seem promising on paper. The Onward may have been a short-lived experiment, but it remains a fascinating chapter in the history of transportation innovation.

Post a Comment for "A Man's 210-Sided Wheel Experiment Goes Wrong"

Post a Comment