Trump Targets Digital Services Taxes: What’s Behind the Backlash?

(Bloomberg) -- Digital services taxes targeting the revenue of big technology companies have returned as a flash point in President Donald Trump’s efforts to rewrite the rules of global trade.

Trump has long argued that these levies are discriminatory against US tech giants like Amazon.com Inc., Google owner Alphabet Inc. and Facebook owner Meta Platforms Inc. During his first term as president, Trump threatened to use tariffs to punish countries imposing digital taxes.

Now that he is back in office, tensions have flared again over who gets to tax the world’s largest firms, and how. Canada was the first to back down in the face of Trump’s ire. It decided to scrap its digital levy in late June — hours before it was due to go into effect — after Trump suspended trade talks with the country over what he called an “egregious” tax. The two countries have resumed talks.

What are digital services taxes?

Broadly speaking, digital services taxes are levies on the revenue that tech companies generate from users in a particular country, from activities such as targeted online advertising, streaming and the sale of data.

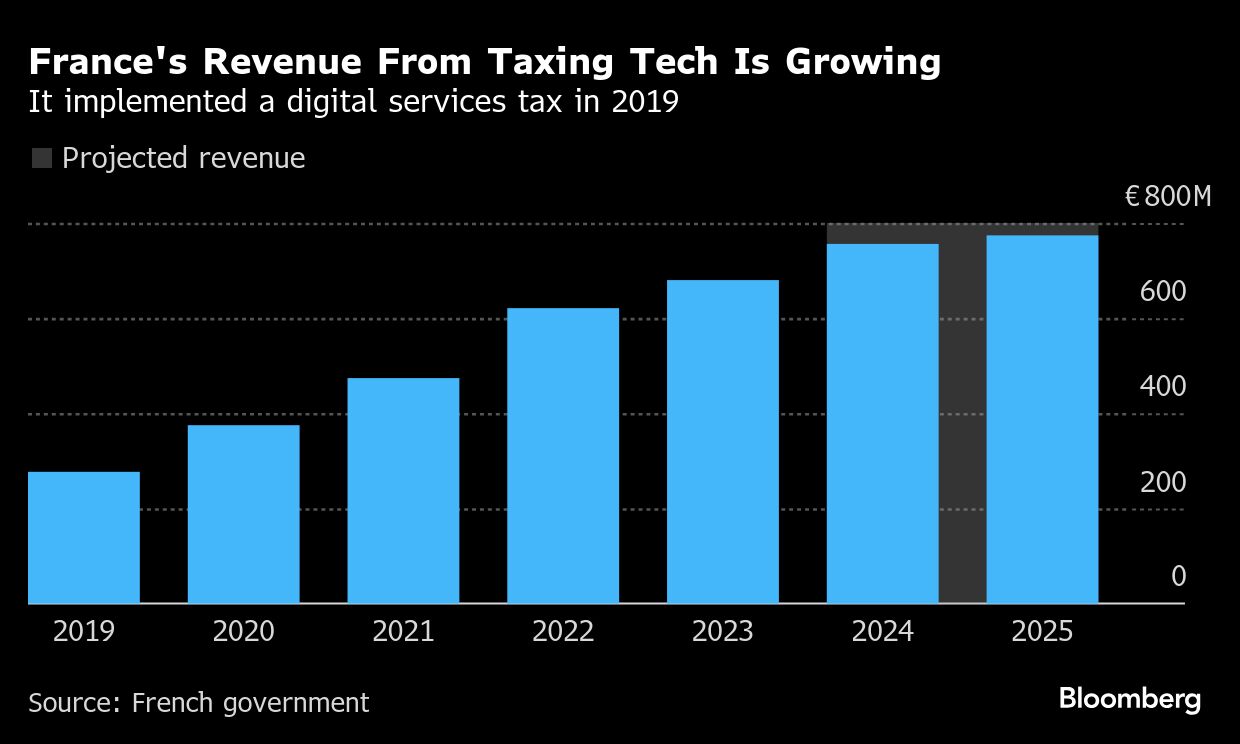

These taxes come in a variety of forms, with different thresholds and parameters. France was among the first nations to implement a digital services tax. In 2019, it introduced a 3% charge on revenue from targeted advertising and other digital services of companies with an annual revenue of at least €750 million ($879 million) globally and €25 million in France.

Other European countries followed, including Italy, Austria, Spain and the UK.

Canada was behind the curve. Its tax was passed into law in 2024 when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was in office. From June 30 of this year, firms were meant to be on the hook for 3% of the digital services revenue generated from Canadian users above C$20 million ($14.6 million) in a calendar year.

Why have countries introduced digital services taxes?

The global economy is becoming more and more digitalized, running on flows of data. But the companies providing services often don’t have brick-and-mortar operations in every country they operate in.

Taxing companies based on their physical presence has thus become an increasingly ineffective method for governments to ensure the tax bills of tech companies match the value they derive from local customers.

Pressure to address perceived injustice in tax systems grew in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, when public outcry over bank bailouts spurred a push to tackle tax evasion.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development — a club of 38 mostly rich countries — has been working for years on a solution to rewrite the rules of how taxing rights are shared among jurisdictions. It has been hosting negotiations with more than 140 countries to adapt the international tax system.

Progress has been slow and regularly set back by the reigniting of trade tensions. Frustrated by the lack of momentum, European countries began to introduce digital services taxes as a stopgap measure — even as they recognized the controversial nature of levies based on revenue rather than profit.

How has the US responded to the digital services taxes?

The US asserts that digital services taxes are less about fairness and more about hobbling American tech firms.

In 2020, the first Trump administration announced plans to impose tariffs of 25% on goods imported from France, including makeup, soap and handbags.

These duties were suspended pending negotiations and the US ultimately reached a standstill agreement with multiple European governments, including that of France. Under this truce, the US shelved its punitive tariffs and these countries effectively agreed to refund any taxes in excess of what corporations will pay once the OECD’s global tax regime is in place.

Shortly after Trump was sworn into office this year, he ordered a reopening of the so-called Section 301 investigations launched during his first term into countries with digital services taxes, and to probe nations that have since developed such levies. These investigations lay the groundwork for the US to retaliate against trade practices it deems unfair to American interests, for example with tariffs.

Trump also instructed the US Treasury to notify the OECD that any commitments the US previously made to its tax negotiations have no force.

How have countries with digital services taxes reacted to Trump’s attacks?

While Canada yielded to Trump, the UK and countries in the European Union have thus far held firm.

When the US struck a trade agreement with the UK in May, it said in a statement that it was “disappointed” that the British government was unwilling to withdraw its digital services tax.

US Treasury Scott Bessent previously said that these taxes were a sticking point in trade discussions with the EU. The EU’s ability to make concessions on this front is complicated by the fact that taxation is a national prerogative for the bloc’s member states, while trade is managed by the European Commission in Brussels.

In February, the French government ruled out undoing its digital services tax to appease Trump. The levy is a growing source of revenue at a time when France’s finance ministry is struggling to rein in the country’s budget deficit. The government expects the tax to bring in almost €775 million this year.

How could the dispute over digital services taxes be de-escalated?

The renewed tensions around digital services taxes will refocus attention on the OECD’s efforts. Many countries have pledged to abolish their digital taxes if there is an international agreement on how to allocate the profits of multinationals for the purposes of taxation.

The hurdles to reaching a deal are high. Numerous treaties would have to be rewritten, and the US would likely lose some taxation rights to countries where its big digital firms operate.

Still, global tech companies have previously expressed support for the OECD’s initiative as a way of avoiding a mushrooming of different tax regimes around the world.

Moreover, as part of work toward a separate agreement on a global minimum corporate tax, the US signed off on a Group of Seven statement in June that spoke in favor of “constructive dialogue on the taxation of the digital economy.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.

Post a Comment for "Trump Targets Digital Services Taxes: What’s Behind the Backlash?"

Post a Comment