Sewage in Your Basement? Plant Proposes Mile-Long Wall to Stop It

Scott Schreiber even admits it — he gets a little too excited about raw sewage.

You can’t blame him. The hearty, gray-bearded executive runs the Camden County Municipal Utilities Authority. It’s one of the largest wastewater management sites in the state, responsible for cleaning and treating the sewage produced by about half a million people, then re-releasing it into our streams and rivers.

To put it lightly, Schreiber is in charge of a whole lot of Number 2.

“One of the things I said to the staff during COVID, obviously everyone remembers the world is falling apart, but what I said to my staff was: ‘I’ve never turned on the TV or read a newspaper or anything where anyone was worrying about if they were to be able to flush the toilet,’” Schreiber remarked, as he took NJ Advance Media on a tour of the massive 35-acre plant he runs.

“That’s a testament to the folks that came to work here. We didn’t miss a day.”

His job’s getting harder, Schreiber says, thanks to something you wouldn’t necessarily think about each time you take a bathroom break: rising sea levels.

The increasing water level could produce more local flooding in the future. Floodwaters could overwhelm the system, making raw sewage back up into basements across his facility’s 36-town coverage area. Or, they could spill the untreated sludge into vital nearby waterways. Schreiber’s crew has been on the hunt for a solution to make sure neither happens.

The fix on the table now? A roughly mile-long flood wall that could be as tall as 12 feet, and ring up a bill of $70 million. Planning is just in the initial stages, and the wall would be part of a larger package of infrastructure updates meant to keep the sewage flowing as water levels rise.

But officials, during a behind-the-scenes look, say things would really start to stink without a long-term solution.

For one, stormwater that accumulates in combined sewer systems in Camden and nearby Gloucester would be bound to overwhelm the plant amid rising seas.

“In January of 2024, we had the highest tide ever recorded on the Delaware (River). This facility did not flood but the whole area around this facility flooded,” Schreiber said. “All the streets were flooded. And so it’s only a matter of time before something like that happens and impacts the actual building.”

“If that floodwater were to come up and enter into the below ground areas, you’re losing function of the plant.”

A flood wall for up to $70M

Emergencies tied to rising sea levels are not a matter of if but of when , experts at the Jackson Street sewage plant said.

Projections from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration , which also consider notable greenhouse gas emission levels, show this part of Camden likely being inundated by roughly 2.5 and 3.5 feet of increased ocean levels by 2100.

“Rain storms are more intense. Storms drop tremendous amounts of precipitation in very small units of time. These storms overwhelm the systems as their capacity is reached quickly,” Schreiber said, noting the max daily flow the plant can handle from cities is 185 million gallons of sewage during storms.

A Rutgers University analysis points to as much as 5 feet of sea level rise in the Camden County region by the end of the century if measures aren’t taken to cut down the amount of harmful gases.

“The CCMUA’s flood wall would be a mile long varying in height from 10 to 12 feet depending on location,” Oleg Zonis, director of engineering at the Camden County Municipal Utilities Authority, told NJ Advance Media at the plant.

Looking down at a miniature of the Camden facility run by about 140 people, Schreiber said one positive nowadays is the county has one plant for the entire region.

Things didn’t always look like that.

“Between the 1950s and the 70s, there were more than 50 wastewater treatment plants all around Camden County,” he said. “And they were discharging (only partially treated) sewage into the very small interior streams of Camden County.”

In the Delaware River specifically, oxygen-starved “dead zones” were even reported.

One of the largest threats to local water treatment today is no longer discharge en-masse, but higher ocean levels and concentrated rainfall. Cue the wall.

“It will be constructed on concrete-filled steel piles approximately 30 feet deep,” Zonis said of the Camden proposal. “Vinyl piles would also be driven around the perimeter to control the water, they are non-structural and will be 15 to 20 feet beneath grade level.”

Talks with the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection and other experts — which began in June — follow a study done in partnership with Drexel University which looked at how combined sewer systems are bound to make sea level rise an even-more complicated issue to tackle.

Combined sewer systems are shared underground pipes that funnel both wastewater and stormwater together to sewage plants like the CCMUA. However during intense rainfall or other kinds of storms, the volume of water can overwhelm the system and send overflow into nearby waterways.

That happened in Newark amid Hurricane Sandy .

With no power for days after the superstorm, that plant was unable to treat its sewage and dumped “hundreds of millions” of gallons of raw waste into the New York Harbor. It was called an ecological catastrophe.

Besides a backup power plant Newark says is needed for storm-related power outages , a seawall has started to take shape at the Passaic Valley Sewerage Authority’s sewage treatment facility, too.

Franco Montalto, a professor in the College of Engineering at Drexel University involved in the school’s study, called rising oceans an issue bound to exacerbate problems storm runoff already causes.

“In my experience, most research on climate change impacts look only at flooding, but do not have the benefit of an all-pipes model of an actual urban collection system in order to look also at combined sewer overflows,” Montalto said in an interview. “The published work also rarely looks at the role that real mitigation measures can have in reducing the scale of the problem.”

He said looking at the issue on a hyperlocal-level can be pivotal.

Like other urban areas in New Jersey, Camden and Gloucester — which together have more than 80,000 residents — are the only two cities CCMUA services that have combined sewer systems today.

That means additional measures are needed.

“As the river continues to rise, (those two cities would have) difficulties in getting the stormwater out of the system via the outfalls during periods of high tide and intense rainfall,“ Schreiber said. “It is likely that Camden and Gloucester will eventually have to install pumps at the outfalls to ensure stormwater continues to flow out of the system.”

Zonis said other investments will be needed to prepare for flooding.

Besides a flood wall for the facility itself, another is planned around an important electrical substation that keeps the sewage plant operating. A February fire from a neighboring Camden scrapyard got threateningly close to engulfing that station and potentially leading to a spill or massive series of sewage backups. The smaller wall around the station will likely not be in place for another four years, however.

The Camden County Municipal Utilities Authority will need another $40 million to $50 million for an interior drainage piping system, pumping equipment and other improvements to harden the site against flood concerns.

“The total cost for this resiliency improvement project is estimated to be $120 million to $130 million,” Zonis said.

He estimated the project would be done in 2029 or 2030 — with two years of planning, designing and permitting plus two more years to build.

But none of that will be possible without money.

‘Insane’ EPA cuts

Preparing for what Mother Nature and federal cuts will mean for how Camden County processes its raw sewage could mean your rates go up — even double for some.

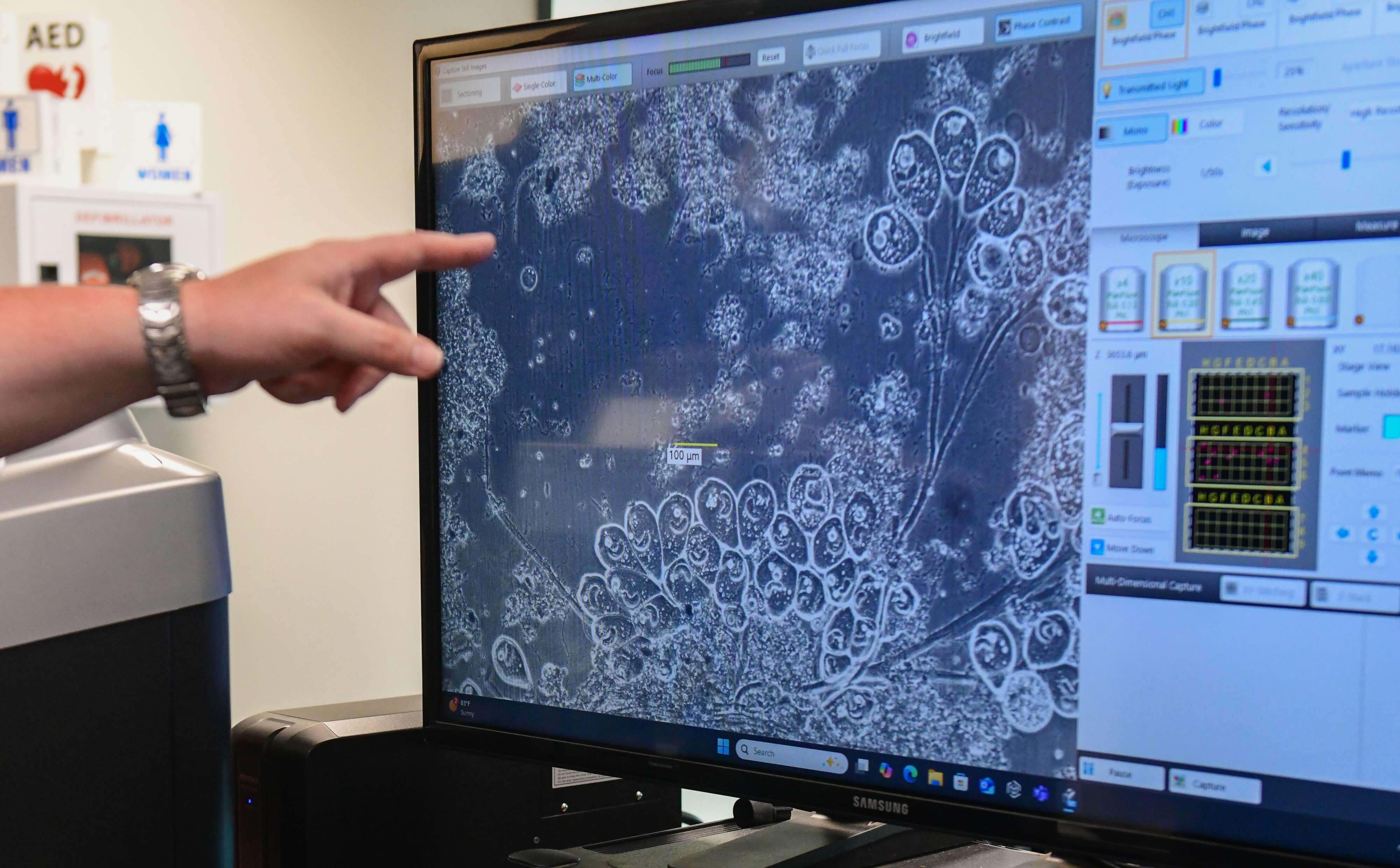

Walking through the plant, Jason Fry, chief of regulatory compliance, discussed operational costs tied to deploying an “uncountable” number of squirmy microorganisms that help break up the sludge at levels you need a microscope to see.

Leonard Gipson, director of operations and maintenance, said it’s not cheap to run the several tanks that cleanse wastewater before it’s considered safe to dispose of.

Not to mention new costs tied to flood-proofing the sizable facility.

Money will be important for it all, Schreiber said.

Cuts to the Environmental Protection Agency are expected from President Donald Trump ‘s administration, county officials acknowledged.

Nonprofit Environmental Protection Network outlined the EPA’s revolving funds for drinking water safety could see a nearly 90% loss. Down from approximately $2 billion to about $300 million, according to the latest estimates.

Officials under Trump, like moves taken against other departments, have called past spending at the EPA “wasteful.”

Camden County Municipal Utilities Authority officials said such a loss “would force the CCMUA to go to market rate interest which would add about $500,000 in interest payments per $1 million borrowed over the course of the loan.”

“I mean it’s insane ...,” Schreiber commented from the treatment plant.

He says ratepayers would have to ultimately pay the price.

Between the CCMUA’s needed operational costs and planned climate-related upgrades, in about five years average one-family homes could see their sewage bills go from $372 a year to as much as $750 to $1,000.

It’s happening in other states.

In Pennsylvania for example, rates are going up 15% and sometimes more in order to keep up with aging infrastructure.

“If something doesn’t change dramatically in the way of thinking in Washington with this particular issue,” a less-enthusiastic Schreiber says, before pausing. “No one knows what that looks like.”

Our journalism needs your support. Please subscribe today to The News Pulse .

Steven Rodas may be reached at srodas@njadvancemedia.com . Follow him on Bluesky at @stevenrodas.bsky.social.

©2025 Advance Local Media LLC. Visit The News Pulse. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Post a Comment for "Sewage in Your Basement? Plant Proposes Mile-Long Wall to Stop It"

Post a Comment