How Vengeful Nazis Hunted Einstein's Cousin Robert, While He Fled to NJ's Safety

LONDON — In the summer of 1937, Robert Einstein — cousin of the world-famous scientist, Albert — purchased Il Focardo, an elegant, beige-stuccoed villa surrounded by olive trees and fields of wheat, 15 miles southeast of the Italian city of Florence.

For Robert, his wife and daughters, life at the 250-acre estate was, his niece later recalled, “paradise.”

Seven years later, however, the family’s blissful existence was shattered in the closing hours of the Nazi occupation when a unit of German soldiers brutally murdered Robert’s family.

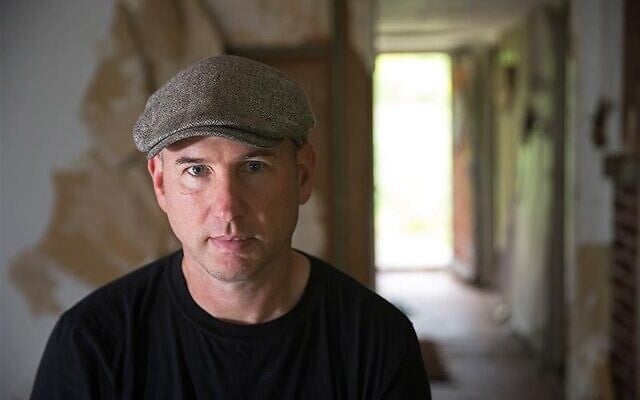

The killings are the subject of “The Einstein Vendetta,” a new book by acclaimed British author Thomas Harding. It explores how, with the Allied forces fast closing in, the Germans sought out the family in their remote, rural idyll — and why.

Harding’s German-Jewish great-grandparents were friends with Albert Einstein and his wife in 1920s Berlin. That personal connection, together with the “fascinating story” of what happened to Robert’s family, was the reason Harding decided to write the book, he told The Times of Israel in an interview.

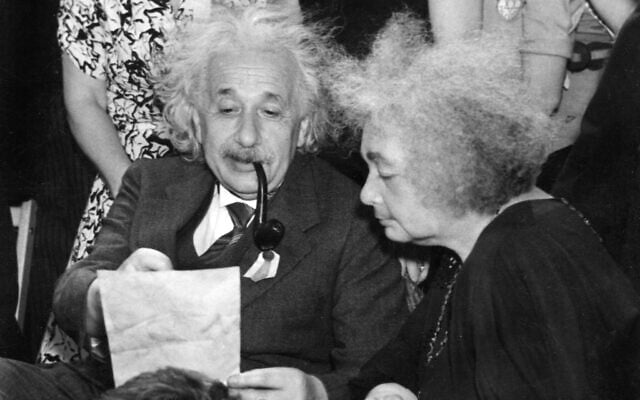

The Nazis’ loathing for Albert Einstein — Germany’s most famous Jew — was no secret. Within months of their coming to power, the news that the German government had put a price on Einstein’s head — offering £1,000, or £430,000 ($580,000) in today’s money — led the front pages of British newspapers. The Nazis went on to revoke his citizenship, burn his books and seize his assets in Germany.

Nor did the regime’s hatred for Einstein dissipate over time. Einstein’s abandonment of his pacifist ideals to actively support the Allied war effort — he publicly donated the manuscript for his theory of relativity to assist a US government war loan drive — meant that “there’s every reason to suspect… that the Nazis’ loathing of Albert Einstein was even more than in 1933,” said Harding. Indeed, Einstein’s name was on a Nazi “black list” of enemies marked for assassination.

However, as he had been since Hitler came to power, Einstein — who had become a US citizen and spent the war in Princeton, New Jersey — was beyond their grasp. So, too, were his sister, Maja, who also lived in the US, and his sons and ex-wife, who lived in neutral Switzerland.

Robert and his family were not so fortunate. They had effectively fallen into the Nazis’ lap in 1943 when, after Benito Mussolini was removed from power and Italy attempted to switch sides, the Germans invaded their erstwhile ally. Rescued from imprisonment, Mussolini was placed at the head of a puppet regime, the Italian Social Republic, in Nazi-occupied northern Italy.

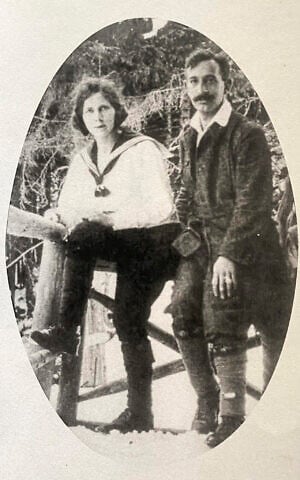

Albert and Robert were close. “He was a first cousin, but he was like a brother to him,” said Harding. Growing up, the boys’ fathers were in business together and, for a time, the two families shared a home in Munich. In all, Robert and Albert, who was four years older than his cousin, lived together for 11 years.

Even when Robert settled permanently in Italy after World War I with his Italian wife, Nina, the friendship survived. Maja and her husband lived in Florence, and Albert, who called his cousin “Bubi” — “little boy” — in correspondence, visited his family in Italy. On Albert’s 60th birthday in March 1939, Robert sent a telegram bearing the words: “Infinite good wishes and memories.”

A month earlier, Maja, had arrived in the US to join her brother. She was part of an exodus of Jews from Florence following Mussolini’s introduction of new racial laws in November 1938. In its first decade in power, Fascist Italy had provided a relatively benign environment for Jews.

Shattered calm

However, Mussolini’s growing alliance with Hitler culminated in the passage of the Nuremberg-style law.

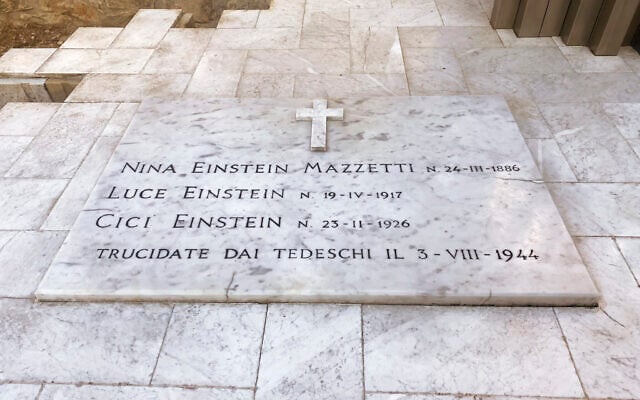

On paper, the Einsteins were affected by the new legislation. Robert and his two daughters, Cici and Luce, lost their Italian citizenship. Nina, who like her daughters was a practicing Christian, retained hers as she had been born in Italy.

Nonetheless, as Harding notes, the racial laws “weren’t really enforced systematically,” with much resting on the attitude of local party bosses and police chiefs. Cici, for instance, remained at high school, while Luce, who was studying medicine in Florence, was able to continue her studies.

The German invasion in September 1943 and the establishment of Mussolini’s new puppet regime days later made the Einsteins’ position much more perilous. In October, the first razzia (or round-up) of Jews in Rome occurred. More soon followed in Florence and elsewhere in Tuscany. And, in December 1943, the minister of the interior took to the airwaves and announced the police were to arrest all Jews and detain them in concentration camps.

Robert and Nina discussed their predicament, but potential escape routes were hazardous. To the north lay the possibility of safety in Switzerland, but the entire journey was through Nazi-controlled territory. If they traveled south, they would, again, have to evade German and fascist forces still loyal to Mussolini before reaching the advancing Allies.

Should the Einsteins have attempted to leave earlier? “These are really hard complicated decisions,” said Harding, who points out that until the German occupation, it was quite common for Jews to attempt to flee to Italy, which was viewed as safer than other Nazi-run neighboring countries.

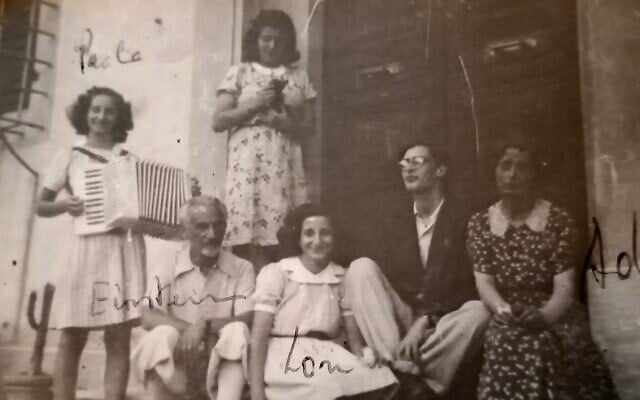

Just over nine months after their invasion, in July 1944, the Germans arrived at the Einsteins’ door, demanding to see Robert. Working in the fields, he had a narrow escape. The family decided to separate: Nina, Cici and Luce — together with Nina’s sister, Seba, and the couple’s three nieces, Anna Maria, Lorenza and Paola — remained at the villa, while Robert took to the nearby woods.

For two weeks, Robert hid out, sometimes sleeping in the open, at other times with local farmers, but never remaining in the same place for more than 24 hours. He fretted constantly about the decision, considering whether it was better to return to the villa.

“He waited in the shadows, paralyzed with anxiety, hoping that something would shift,” writes Harding. Apart from an occasional prearranged meeting with Nina, Robert’s only comfort was the noise of the Allied planes, gunfire and artillery shells, which suggested that salvation was close at hand.

The family nearly made it. Early on August 3, with the BBC reporting that the Allies were barely 20 miles from Florence, seven heavily armed German troops arrived at the villa and smashed open the doors. The commanding officer, who was in his 30s, demanded to know Robert’s whereabouts. Nina remained silent.

For the next 14 hours, the Germans held the women in the house — initially in the cellar with the estate’s farmworkers, and later in an upstairs bedroom. They could hear the troops searching the house, laughing raucously and playing the piano.

Later, the Germans led the women through the vandalized villa, telling them dynamite had been discovered in the basement, and accusing them of aiding the partisans. Nina, Luce and Cici were taken away and questioned in turn.

Nina’s admission that her husband was in the woods and Luce’s false claim that she owned the dynamite — as the Germans well knew, they themselves had planted it — could not save them. From upstairs, Seba and the Einsteins’ nieces heard screams and gunfire.

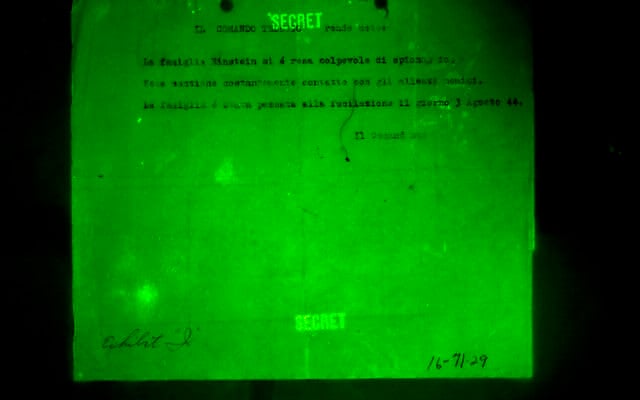

The next morning, as a local priest viewed the “dreadful, horrifying” scene, British soldiers arrived at the villa. In the house, printed notices left by the Germans were found, declaring that the Einstein family was guilty of espionage and had been duly executed.

Wracked by guilt — he endlessly questioned what would have happened if all the family had hidden in the woods — Robert was suicidal. Encountering a partisan unit, he asked its commander whether he could borrow a pistol to kill himself.

He failed on this occasion but, less than a year later, in July 1945, 61-year-old Robert took his own life by swallowing 23 sleeping pills. A local priest who had been close to the Einsteins later said that with Robert’s death, the family had been “totally annihilated by Nazi ferocity.”

Spontaneous or premeditated?

Harding’s book wrestles with the question of whether the Einsteins’ murder was, as one Italian historian who investigated the case later concluded, a spontaneous “episode of gratuitous violence,” or a more calculated, planned act of vengeance against the only members of the famous scientist’s family the Nazis could lay their hands on.

Like the family and local people, Harding believes it was the latter. He points to the fact that the notices left at the villa accusing the Einsteins of espionage had been duplicated and printed by the Germans before they arrived at the house, suggesting that the killings were “premeditated.” It is telling, notes the author, that only those with the surname “Einstein” were questioned and murdered by the Germans. The perverse “logic of a spontaneous act of violence,” he believes, suggests that Robert’s sister-in-law and nieces would also have been massacred.

Eyewitnesses also provided testimony that in the weeks and months before the murders, German soldiers were looking for Robert.

Moreover, evidence suggests that the Nazis were not rounding up Jews in Florence in the summer of 1944 — and especially not in the occupation’s final days — and that other Jews living locally were not targeted at that time.

This, of course, raises one of the greatest mysteries surrounding the killings. “Why, just as the Allies were pushing into the area, did a small unit of German soldiers go out of their way to travel to a remote villa outside of Florence to track down Robert Einstein and his family?” asked Harding.

Official investigations carried out by German and Italian prosecutors over the past two decades have concluded that the soldiers would only have come to the villa on the strict instructions of their superiors. Experts agree. Historian Christian Jennings, for instance, argues the order to kill the Einsteins “almost certainly” came from Berlin.

“There was an efficiency to it, a clarity and precision to it,” Harding says of the killing. “That to me feels like an order.”

Whether that order came from Hitler or one of his lieutenants, such as Himmler or the deputy head of the SS, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, remains a mystery. So too does the name of the German officer who commanded the unit at the villa.

Indicating that they also believed the killing was a political act of reprisal aimed at Albert Einstein, the Allies sent war crimes investigators to the scene shortly after the murders. They took statements from Robert and Seba, and the case was later passed to the Italian authorities. Italy’s woeful record on pursuing war criminals meant that there was no serious effort to examine the case until the turn of the century.

Three possible suspects — Panzer regiment battalion commander Cpt. Clemens Theis, parachute brigade Maj. August Schmitz, and Sgt. Johann Riss — have been probed by German and Italian prosecutors over the last two decades. Riss was positively identified by Lorenza and had also been found guilty by an Italian court of participating in a massacre near Florence in which 174 civilians were murdered days after the Einstein killings.

Nonetheless, Harding accepts — albeit with frustration — that the passage of time means the identity of the officer will likely never be proven nor justice done. Instead, he argues, it is important to focus on the bigger picture.

“We have this obsession with being able to point our fingers at individual perpetrators for understandable reasons,” he said. “But perhaps more important … from a victim’s point of view, what’s important here is that the Germans were responsible. They went out of their way to get the family.”

Denied justice, the Einstein family has suffered a further twist of the knife since the book’s publication. Two years ago, Paola’s daughter, Eva Kosloski, filed a claim for €250,000 ($284,000) from a fund established by the Italian government in 2022 to compensate victims of Nazi war crimes. Last month, however, Kosloski’s submission was rejected on the basis that she couldn’t claim on behalf of her great-aunt and second cousins.

The claim was not about the money, Kosloski had said, but about “the Italian and German governments finally acknowledging this terrible war crime … [and] the lasting damage it has caused my family.”

The post With Albert Einstein safe in NJ, how vengeful Nazis hunted down his cousin Robert appeared first on The Times of Israel .

Never miss important Israel stories - get the free Times of Israel Daily Edition

Post a Comment for "How Vengeful Nazis Hunted Einstein's Cousin Robert, While He Fled to NJ's Safety"

Post a Comment