'The Determined Spy': The Meteoric Rise and Fall of a CIA Icon

Frank Wisner—a legendary figure at the Central Intelligence Agency and a principal designer of its clandestine activities—poses a challenging subject for any biographer. Detractors of the agency may portray him as an unfeeling operative who showed little hesitation in employing harsh tactics to uphold America’s global dominance. Conversely, some might examine his final days, marked by struggles with bipolar disorder, and formulate extensive hypotheses regarding how his psychological state influenced broader aspects of U.S. international relations.

In "The Resolute Agent," Douglas Waller steers clear of these pitfalls. He provides an intricate and balanced account of Wisner's significant influence within the nascent CIA as well as his illness, allowing readers to form their own opinions.

Essentially, Waller presents dual narratives: The majority of the book focuses on Wisner’s career trajectory, detailing his exploits within the CIA’s predecessor organization during World War II—the Office of Strategic Services—as well as his pivotal involvement in the U.S.-supported regime changes in Iran and Guatemala in 1953 and 1954 respectively. This account delves deep into an extensive historical backdrop, largely sourced from newly released CIA documents that encompass all aspects ranging from internal power struggles to high-level discussions concerning international diplomacy.

The final sections detail how swiftly everything crumbled thereafter. Admitted to an institution in 1958, Wisner received electroconvulsive therapy and experienced some relief for several years until conditions deteriorated once more. Dismissed from his job and subsequently compelled into retirement, he ended his life in 1965—committing suicide at his family property in Maryland. These poignant accounts predominantly stem from conversations between Waller and Wisner’s relatives, particularly his offspring.

CIA pioneer

Raised in affluence and wed to an energetic socialite named Polly Knowles, Wisner appeared to lead a charmed life as he embarked on his legal profession with a prestigious Manhattan-based firm. However, corporate law quickly became tedious for him. In 1943, "Wild Bill" Donovan offered Wisner the opportunity to contribute to the war effort by joining Donovan’s secretive organization—the OSS—which was simply irresistible.

Serving covertly as a Navy lieutenant commander, Wisner excelled as a brilliant organizer — initially dispatched to Cairo, subsequently to Istanbul, and ultimately to Bucharest, Romania, where he headed a unit supplying military intelligence to Allied troops without raising Soviet suspicions.

In Bucharest, Wisner's perception of the Soviet menace intensified when he witnessed the Red Army ruthlessly loot the nation and transport Romanian citizens via train to the U.S.S.R., consigning them to lives of forced servitude. Without knowledge of the covert agreement between Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin to designate Romania as part of the Soviet sphere—a move intended for Britain to retain control over Greece—Wisner viewed the nation merely as collateral damage due to Allied indecisiveness. This disillusionment stayed with him throughout his life.

Following the conflict, Wisner's reputation kept growing. He collaborated closely with Allen Dulles, who would become both a trusted confidant and an essential partner before ultimately becoming his superior as head of the CIA. This period saw him relocate to Washington where his timing proved fortuitous; President Harry S. Truman disbanded the OSS but soon recognized the necessity for espionage activities amid shifting global dynamics. The president prioritized information gathering and assessment over clandestine missions, yet Wisner managed to secure a position at the helm of a newly formed entity—the Office of Policy Coordination—which later evolved into the core framework of American undercover strategy encompassing economic and political battles, psychological operations ("psyops"), and propaganda efforts.

Starting from this point, Wisner initiated significant "soft power" initiatives like the Congress for Cultural Freedom and Radio Free Europe. However, the OPC met with limited success when supporting anticommunist insurgent organizations within the Eastern Bloc, an area dominated by the extensive Soviet intelligence network which overshadowed U.S. capabilities. Despite these challenges, Wisner’s standing grew substantially by 1952, leading him to author a pivotal report known as the Magnitude Paper. This document, endorsed by President Truman, advocated for expanding covert activities significantly. In conjunction with this restructuring, Dulles was promoted to become the deputy director of the CIA, whereas Wisner took up the role of the agency’s deputy director for plans, managing all aspects of the secret services.

The Georgetown set

Meanwhile, Frank and Polly Wisner were stars on the D.C. social scene and core members of the “Georgetown set” that included their close friends Katharine and Phil Graham, the owner of The Washington Post. Wisner worked hard and partied hard, and as his duties at the CIA grew, cracks began to show: Nonstop talking, erratic mood swings, heavy drinking, crushing hours fueled by adrenaline but little sleep. Because these were typical qualities of Washington strivers, his friends tended to see these blips merely as signs of pressure.

The shift in administration during January 1953 marked yet another pivotal moment. Despite Harry S. Truman fostering the growth of the Central Intelligence Agency, both he and Secretary of State Dean Acheson harbored doubts regarding extensive American involvement overseas, particularly within newly independent countries following colonial eras. In contrast, President Dwight D. Eisenhower supported utilizing the CIA to advance U.S. diplomatic goals through what he perceived as a more cost-effective and minimally violent alternative compared to deploying armed forces—provided he remained somewhat uninformed about specific details.

Wisner and Dulles took advantage of the situation. The CIA was already considering two nations—Iran and Guatemala—for potential regime changes supported by the U.S., but Eisenhower's approval provided the necessary clearance for action.

Both countries were led by leaders chosen through democratic elections, though they maintained weak connections with the Soviet Union—these links were sufficient for the CIA to depict them as menacing communist adversaries. However, the primary driving force was actually big business: Britain aimed to sustain British-Iranian Oil Company’s firm control over oil profits, whereas United Fruit intended to preserve its strong dominance over banana cultivation in Guatemala.

Historians nowadays largely agree on the grim long-term consequences of these two operations, which are regarded as some of the most shameful blemishes on both the CIA’s record and Eisenhower’s presidency. Waller aligns with this perspective. However, he also underscores how uncritically Congress and the media accepted these events at the time. The use of misinformation for partisan gain and the flouting of legal norms hardly caused any concern among people back then.

A rapid descent

As soon as conditions started worsening, they declined rapidly. Following the unsuccessful Hungarian revolt and the Suez Canal crisis in 1956—which Waller views as significant pressures rather than root causes—Wisner's erratic conduct escalated dramatically after being worn out by espionage duties. Agreeing with his kinfolk, he entered Baltimore’s Sheppard Pratt Institute seeking help, undergoing electroconvulsive therapy there. This intervention proved effective temporarily; indeed, the CIA reassigned him to serve as station chief in London. Nonetheless, it became evident that his illustrious career had reached an end. Upon returning stateside, Wisner underwent more electroshock treatments while gradually reducing his involvement with the CIA due to reduced capabilities. In 1963, he faced yet another devastating setback upon learning about the death of his close confidant Phil Graham—who battled manic depression himself—and chose suicide, thereby passing leadership of The Post onto his spouse.

Ultimately, when Wisner chose to take his own life, he found himself nearly entirely isolated. His unpredictable conduct had pushed away most of his acquaintances, his career with the CIA had come to an end, and his spouse was exhausted.

A few years afterward, during a talk with Katharine Graham—who had become a close confidante after sharing a profound sorrow—Polly attempted to unravel everything, according to Waller’s account. Polly noted that their spouses couldn’t "stomach living as though they were accomplishing nothing," adding, “they simply couldn’t stand it.” not "being at the heart" of the nation's matters.

Helen Fessenden serves as an assignment editor for the financial section at The Washington Post.

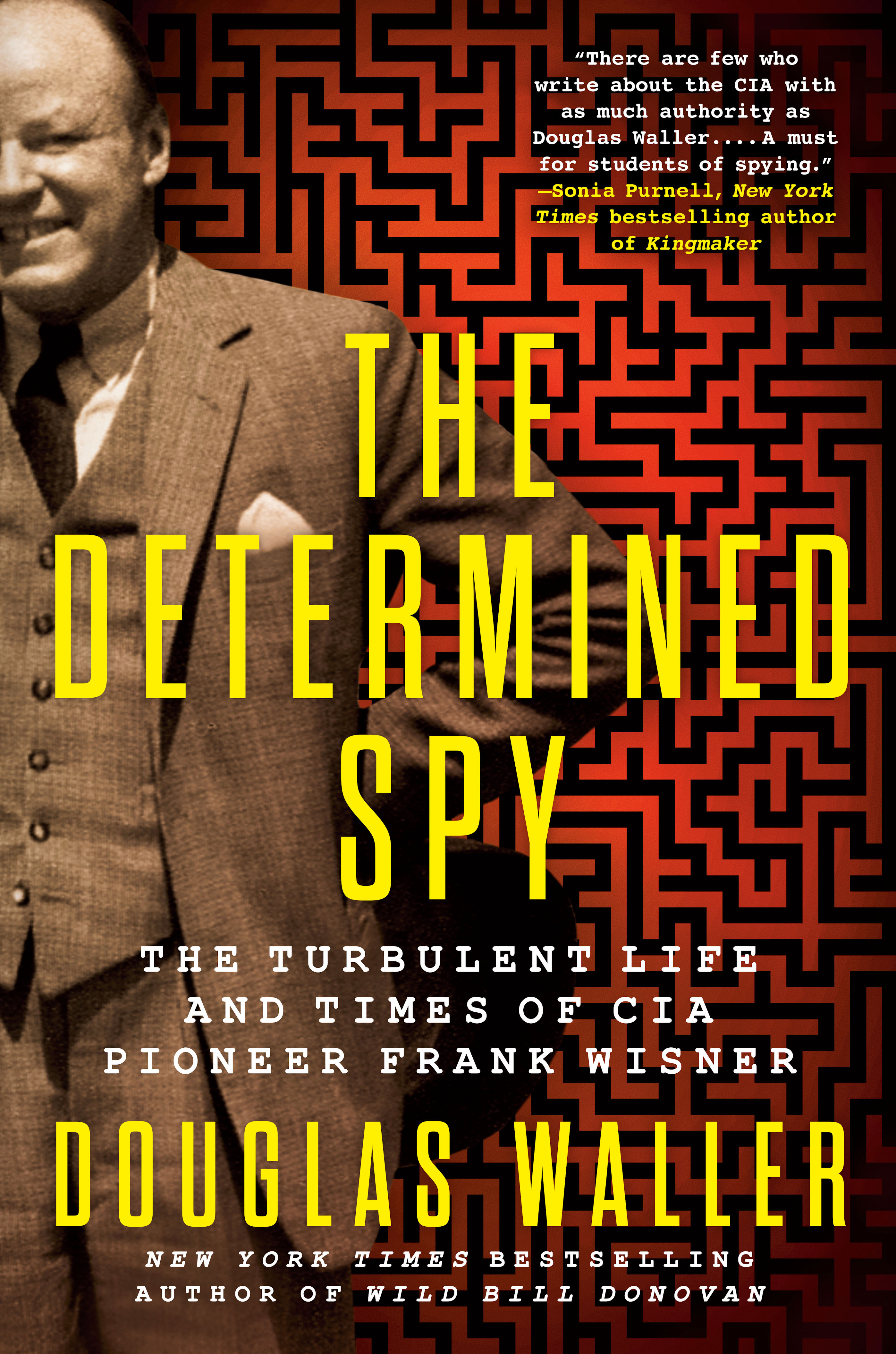

The Determined Spy

The Chaotic Existence and Era of CIA Trailblazer Frank Wisner

By Douglas Waller

Dutton. 656 pp. $36

Post a Comment for "'The Determined Spy': The Meteoric Rise and Fall of a CIA Icon"

Post a Comment