New Report Reveals: Vending Crackdown Targets Poor minorities in White Suburbs

Waleed Salama dedicated two years to understanding vending rules before launching his own Halal cart on Eighth Avenue in Midtown Manhattan back in 2002. Every day, except for one, he commutes from his residence in Coney Island to operate his business. However, despite all this preparation, the 59-year-old mentioned that these efforts seldom shield him from fines, particularly over the past couple of years when inspections became more rigorous.

The police visit daily and issue tickets. Sometimes, they may hand out multiple tickets to the same person within one day," explained Salama, holding a vending license since moving to the city from Egypt in 2000. "No matter what, they'll always manage to find something to cite you for. When I inquire why this happens, 'What’s your reason?' they respond with, 'I have orders; it isn’t personal—it's just part of their directive.'

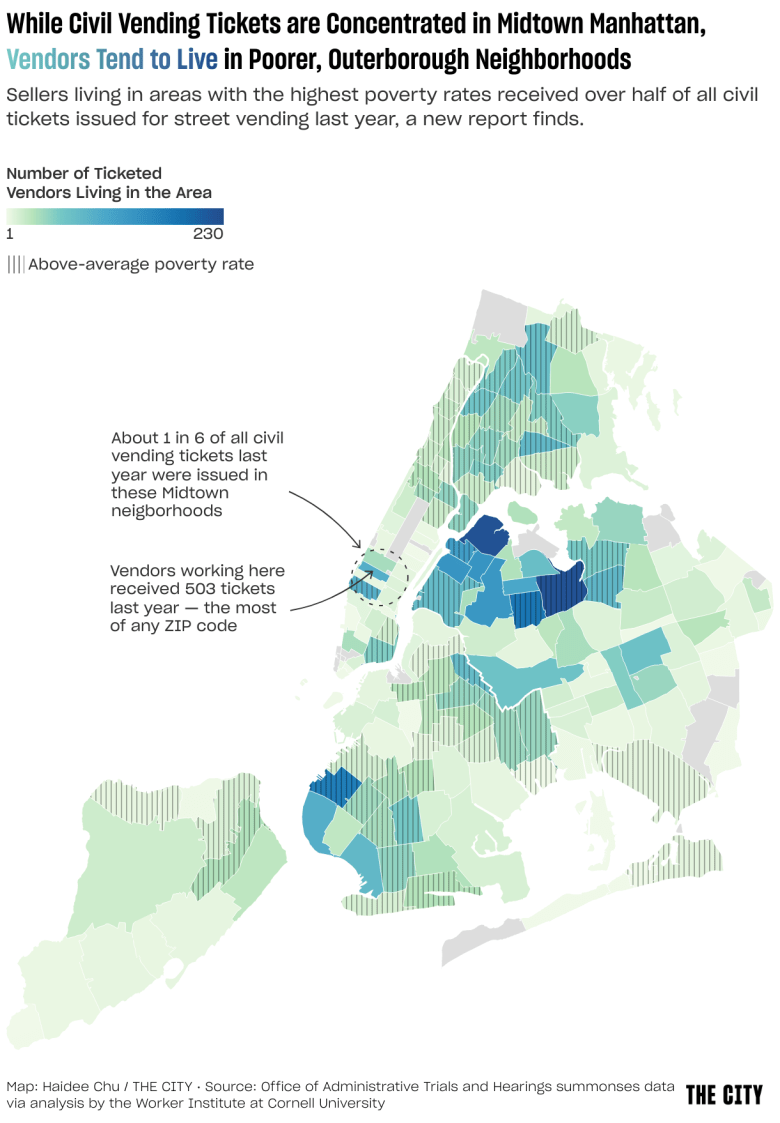

Salama’s story mirrors that of numerous street vendors in New York City. Most vending citations tend to be issued in mostly white and affluent areas against immigrants and minorities who reside in significantly less well-off outer borough neighborhoods, as reported. a new report by the Worker Institute at Cornell University.

According to an analysis of summonses data from several municipal agencies, more than half of the civil citations for sidewalk vending in 2024 were given to vendors residing in areas within the city that have the most significant levels of poverty.

The highest number of criminal vending summonses was concentrated in four regions located within Midtown, specifically between 25th and 60th Streets along Fifth Avenue extending westwards. Similarly, two out of the top five ZIP codes for issuing civil citations also fell into this area. According to census information referenced in the report, all these Midtown ZIP codes have lower proportions of non-white inhabitants compared to the overall city average.

In contrast, the top five ZIP codes with the highest number of vendor addresses receiving civil summonses were located in Astoria, Corona, and Elmhurst within Queens, along with Sunset Park in Brooklyn. Three out of these four areas have larger populations of non-white and immigrant residents, as well as higher poverty rates compared to the city’s average. (It should be noted that NYPD public data for criminal summonses do not disclose residential addresses for vendors.)

The report asserts that "this portrays an costly initiative aimed at criminalizing immigrant and minority groups mainly for functioning in largely white areas."

The research emerges as the quantity of citations for sidewalk vendors keeps rising despite several highly publicized clampdowns by Mayor Eric Adams' government, including Operation Restore Roosevelt in Corona.

Overall, according to City Limits Last year, the NYPD and the Department of Sanitation issued 13,520 tickets related to street vendors, which is more than twice as many as the 5,748 citations they gave out in 2023. The DSNY reported this increase. emerged as the main agency responsible Regarding vendor enforcement in April of that same year, although the police department continued to play a significant role in issuing tickets alongside the parks and health departments.

“The consequences are an extremely intricate network of rules and administrative procedures that this predominantly low-wage immigrant workforce has to deal with, as noted by the authors of the Cornell study. They also pointed out that due to the complex system of enforcement involving various agencies, significant amounts of time, funds, and assets are dedicated to regulating street vending activities,” they explained.

The report similarly describes the sanitation department’s enforcement efforts as "expensive and inefficient."

Last year, DSNY levied approximately $200,000 in fines related to vending activities; however, they managed to collect only $91,000 out of this amount despite investing $2 million into enforcing regulations against street vendors. According to the report, this equates to around $21 wasted for each of the 1,502 vending citations handed out by the department.

Although the parks, health, and police departments also distribute vending tickets, no other organization supplied particular spending information related to these initiatives.

The DSNY press secretary, Vincent Gragnani, stated that generating funds is not the objective of their enforcement activities.

We have frequently stated that we do not pursue enforcement for possible income," Grangnani remarked. "The purpose of enforcement is to make sure individuals adhere to current regulations. It would bring us great joy if everybody followed the law and we didn’t have to impose any penalties.

Supporters contend that lawmakers and regulatory bodies ought to focus on reforms which they believe could generate income for the municipality as well as increase chances for sidewalk sellers.

Carina Kaufman-Gutierrez, who serves as the deputy director of the advocacy organization Street Vendor Project, pointed out a report from the city’s Non-Partisan Fiscal Analysis Bureau last year that found a bill to eventually lift the caps on vending permits would generate $17 million in net revenue for the city.

“If the city is losing money on a policy that also pushes New Yorkers further into poverty and destabilizes them, when they’re also now presented with an opportunity to actually create jobs and formalize a system, that to me seems like a very clear choice on creating a policy that’s both beneficial to the city’s coffers but also supports our city’s smallest businesses,” Kaufman-Gutierrez said.

The City Council, where many members have pushed to reform the vending system rather than increase enforcement, notably proposed allocating $7.7 million in its preliminary budget response for the coming fiscal year “to expand and formalize a permanent Vendor Enforcement Unit” at sanitation. The department’s unit included 84 officers, 24 lieutenants and three inspectors as of November 2024.

Council spokesperson Julia Agos told THE CITY its funding proposal “seeks to ensure adequate staffing needed to thoughtfully and equitably approach” street vending issues.

“Street vending is a vibrant part of our city’s culture and economy, and it must operate in a safe and fair manner,” Agos said. “Effective enforcement should not mean overly relying on fines or engaging in the destruction of property, but rather ensuring compliance in a way that both supports the quality of life for all New Yorkers and the ability of New Yorkers to make a living.”

‘What’s the Point of It?’

While most vending tickets last year were issued for unlicensed vending, “quality-of-life” infractions such as improper setups were also frequently penalized, the report noted.

Vendors, however, say those rules are arbitrarily enforced — another sign of ineffective enforcement that perpetuates harm towards sellers through what the report calls “myriad and often confusing regulations.”

Salama, for one, said he once received an NYPD criminal ticket for failing to display his vending license while he was still setting up shop for the day. Another time, he was hit with a criminal summons for operating from within 15 feet of a fire hydrant — a rule which This only pertains to merchandise vendors. , as municipal regulations overseeing street food sellers Only ensure that their shopping carts do not come into contact with or rest against hydrants.

Many times when I appear at Criminal Court, the charges often end up being dropped because they were frequently filled out incorrectly by the police," Salama explained. "The issue lies in having to personally show up for court appearances, as this causes me to miss an entire day of work.

These days, he added, ticketing and time lost to attending court can eat up about 30% of his vending income.

Birane Ndiaye, another Midtown seller, thought his troubles with vendor enforcement would slow down when he received a merchandise vending license in 2015 to sell accessories like hats and sunglasses after spending 21 years on the waitlist. (The city has for decades capped those licenses at 853 for non-veteran sellers, leaving more than 11,900 people on a waitlist .)

However, enforcement from the sanitation department has intensified, particularly since the start of this year, as noted by Ndiaye. He has consistently made an effort to steer clear. areas where vending is prohibited , he added, but has nonetheless received two tickets so far this year for violating those rules while selling outside of the restricted areas as indicated in a booklet he received from the city when he obtained his license.

“Most of the time they don’t even pay attention to where I’m vending. Wherever I go, they will come,” said Ndiaye, who moved to the city from Senegal in 1988. “Everyday I wake up, I just put in my mind that I’m going to get a ticket.”

While those two tickets have cost Ndiaye just $25 a piece so far, the 61-year-old said it cost him $250 — equivalent to two days worth of income on a good week — to reclaim confiscated goods from the sanitation department, and another $100 to rent a vehicle to transport those items back to storage.

I've struggled with paying my rent since I had to use the funds set aside for it to reclaim my belongings," explained Ndiaye, who shares an apartment in Harlem for $620 per month. "If the city issues us a license yet doesn’t permit selling in places where we could actually earn income, what’s the purpose of having one? Is the city aiming to push street vendors into homelessness?

Gragnani, who serves as the sanitation spokesperson, stated that his department neither formulated the regulations governing street vendors nor established the associated penalties; instead, they aim to uphold these pre-existing rules. Additionally, he mentioned that various entities frequently request their intervention, including local politicians, neighborhood councils, commercial enhancement organizations, and public complaints made through the 311 system.

“These requests and our enforcement work are rooted in the belief that all New Yorkers, across every neighborhood, in every borough, deserve clean, safe sidewalks,” he added.

Fruit vendor Johirul Islam, for his part, said he recently received a $250 ticket from DSNY for a napkin on the ground he said wasn’t even from his business. He was also fined $25 two months ago for adding an extra layer of protection on top of an umbrella that covers his cart.

“They issue you tickets no matter what, even if it’s not in any law that we know of,” said Islam, who commutes from Ozone Park at least five days a week to set up shop on the Upper West Side, where he’s been working for the past 25 years. “We always joke among ourselves that sanitation police are not happy until they issue tickets.”

One of his neighboring fruit vendors, he said, recently closed up shop after receiving a summons, while another is planning to do the same.

“I’d drive by and I wouldn’t see them anymore,” said Islam, an immigrant from Bangladesh who is contemplating whether he should forgo vending altogether and try to make a living as a yellow cab driver instead.

“I feel bad that my friends are all moving away, because it could be me anytime.”

Our nonprofit newsroom relies on donations from readers to sustain our local reporting and keep it free for all New Yorkers. Contribute to THE CITY now.

The post New Report Reveals Vending Crackdown Harms Impoverished Minorities in Predominantly White Areas appeared first on THE METROPOLIS - NYC News .

Post a Comment for "New Report Reveals: Vending Crackdown Targets Poor minorities in White Suburbs"

Post a Comment