A New History Revives the Untold Stories of Chinese Immigration

Within my family, stories of anti-Chinese discrimination have been handed down through generations. Over a hundred years back, my great-grandparents, Wallace and Tungert Chong, had to obtain special permits—essentially visas—to journey from Hawaii to the continental U.S., despite being American citizens. Ten years afterward, a white college advisor prohibited their son, my grandfather Walbert Chong, from sitting for the MIT entry test due to his nearly perfect academic record; the advisor claimed that he would not be compatible with the institution's environment. Two decades later still, kids bullied my mom by calling her names like "chink" when she went to and from primary school.

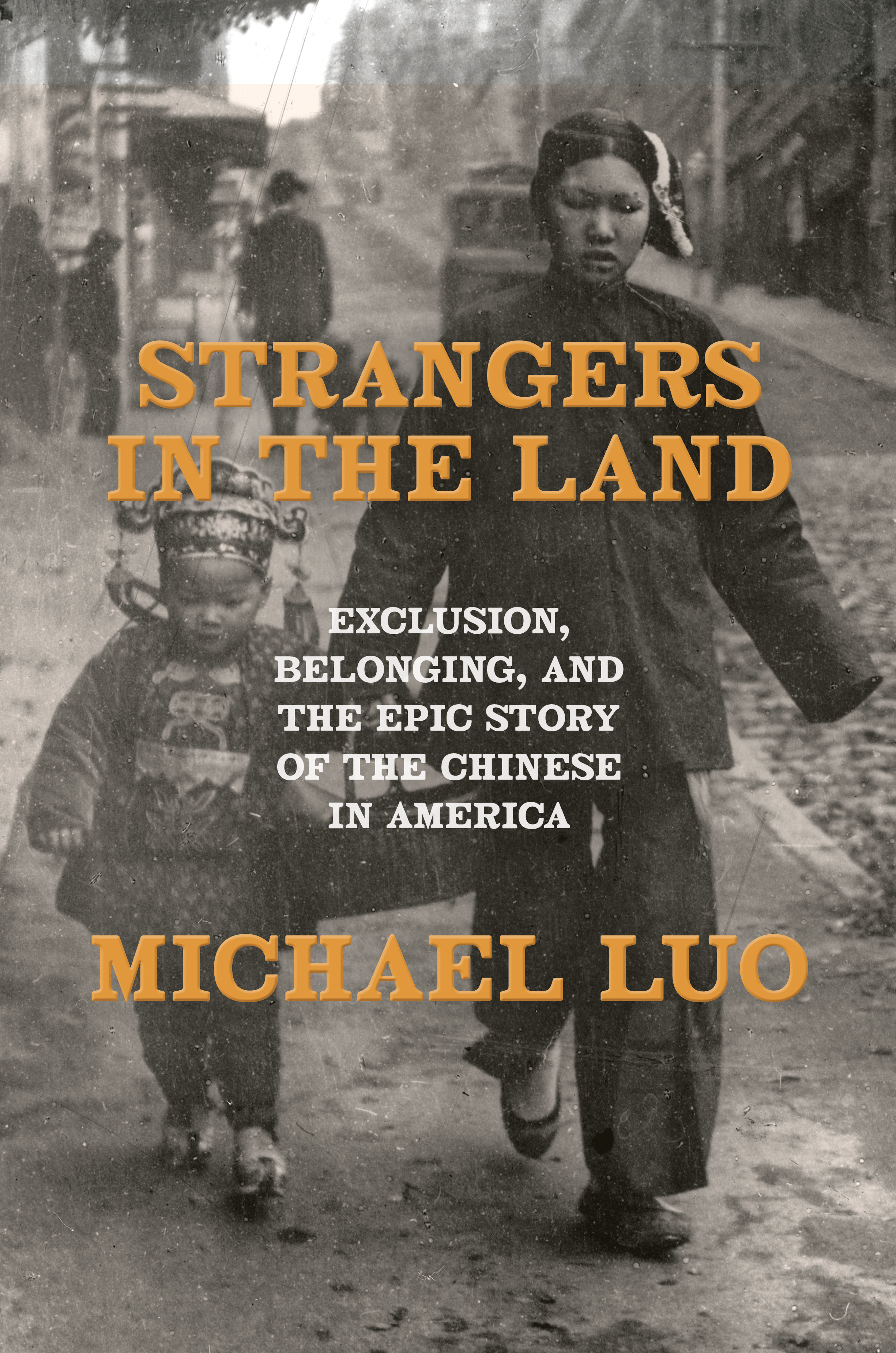

Ask any Chinese American, and they'll likely share personal experiences with harassment and racism. The New Yorker editor Michael Luo mentions that his upcoming book tackles this issue. Strangers in the Land: Exclusion, Belonging, and the Grand Tale of the Chinese in America, Came into prominence following an incident in 2016 when a woman confronted him on the streets of Manhattan. Post-church service, as he stood in the rain alongside his family and several friends, another person pushed through irritably, annoyed at being obstructed. A short distance later, this individual returned and shouted, "Go back to China!"

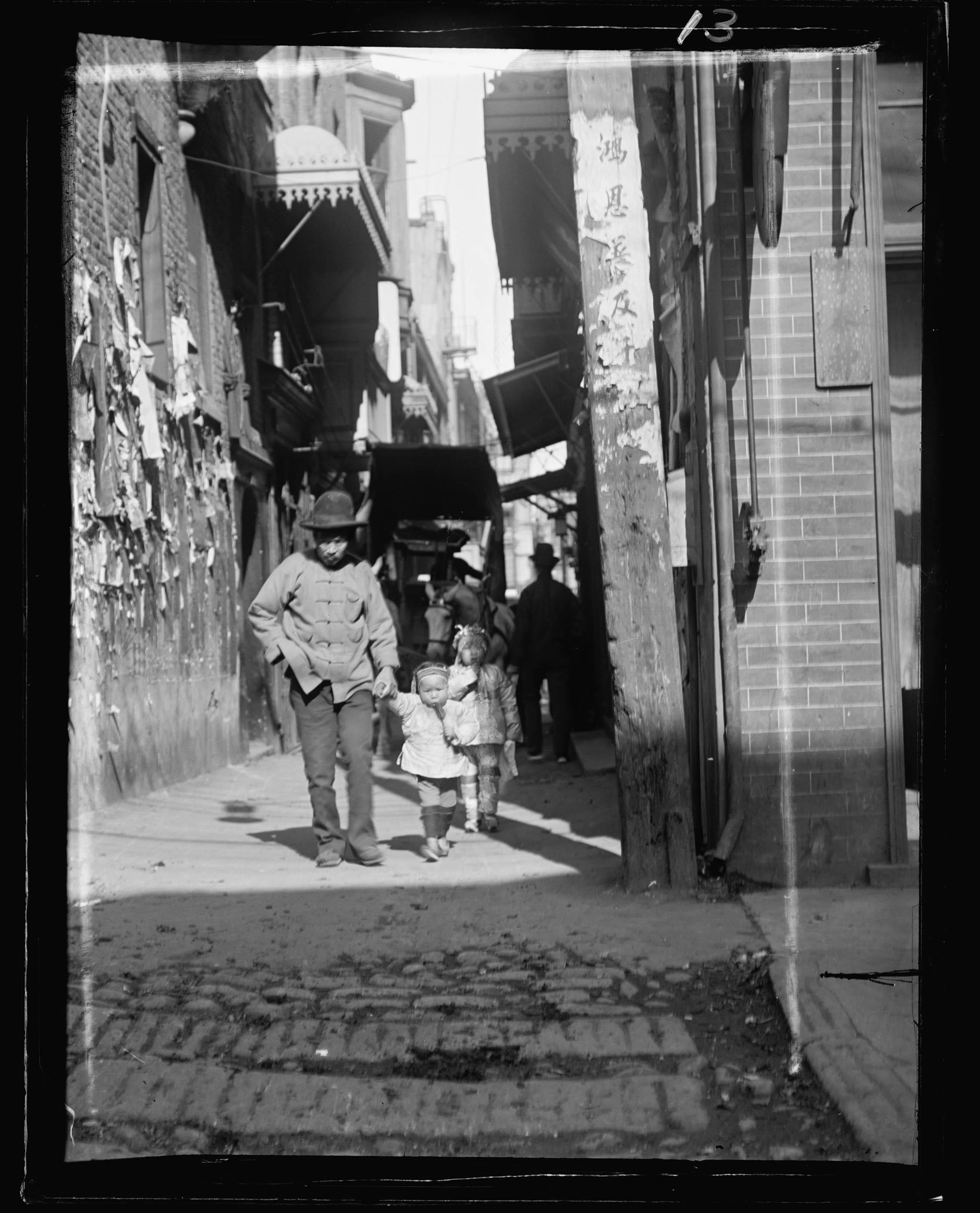

"Strangers in the Land" explores the extensive history of Chinese people in America, partly to understand why racism was so prevalent. The book begins with tales of gold. Although nobody is sure how reports of shimmering particles in American rivers made their way across the Pacific during the mid-1800s, these rumors led many young, aspiring Chinese men to travel to California. During those exciting times in the Wild West, the Chinese swiftly adapted to their new circumstances, either seeking fortune through mining or finding work as chefs, manual workers, and house staff.

America would predominantly respond to them with aggression and harsh criticism, casting them into the "cauldron of racism and exclusion." It shouldn’t be astonishing that the repercussions resonate through families such as mine. As Luo points out, "The uncertainty surrounding the Asian American experience has never truly diminished."

On certain occasions and within specific regions, local leaders embraced Chinese immigrants initially. In 1850, San Francisco organized an official event to honor the city’s newest inhabitants. Entrepreneurs in California anticipated a prosperous era of commerce linking America with China, where migration played a key role as part of this exchange.

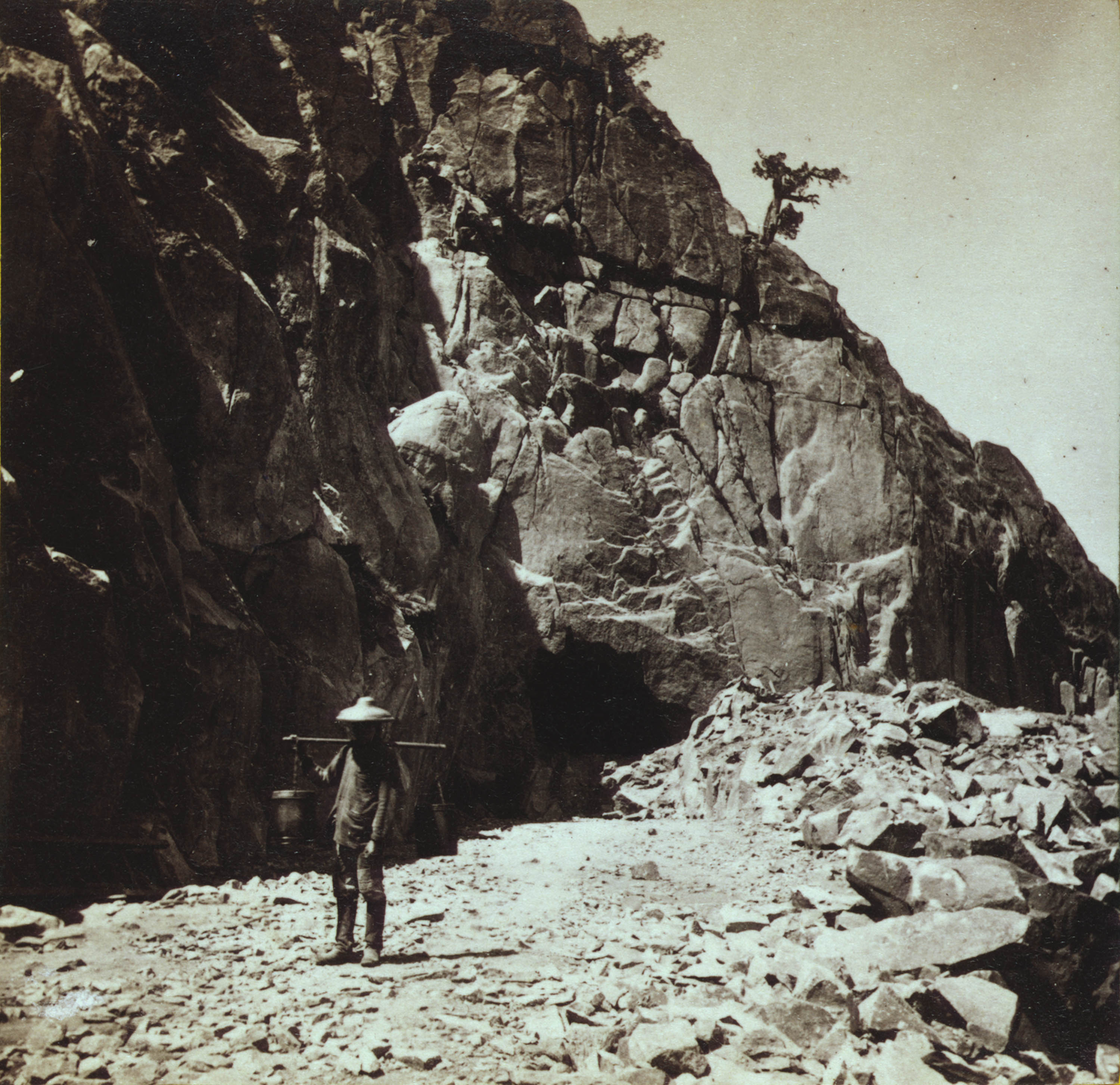

As major American railroad companies hastened to install tracks, they relied heavily on the Chinese laborers, who demonstrated remarkable skill and efficiency. These workers handled 560-pound rails with ease, drove spikes firmly into position, and bored holes into solid granite to detonate explosives for tunnel excavation as the railway lines steadily advanced. During a celebratory dinner marking the conclusion of the vast network, both railroad officials and journalists cheered heartily, acknowledging the crucial contribution made by these Chinese workers.

However, this positive sentiment soon waned. When an economic decline began in the 1870s, both political figures and organized labor found a convenient scapegoat. In Washington, decision-makers harbored nebulous concerns that granting voting rights to Chinese "pagans" and "heathens" might disadvantage white workers and threaten American values. A strategy employed to prevent their enfranchisement involved denying them access to naturalization processes. This exclusionary policy became law through the enactment of the Naturalization Act of 1870. That legislation provided opportunities for citizenship to individuals who were either born in Africa or descended from Africans but explicitly excluded those of Asian origin—keeping the Chinese without a path to citizenship for over sixty years.

With calm and measured writing that matches the terror he conveys, Luo details the violence along the West Coast in the ensuing years. Fueled by sensationalist newspapers, lax law enforcement, and an uncaring populace, groups of white laborers carried out lynchings and executions against Chinese immigrants. In a particularly harrowing passage, Luo recounts a lynching in Los Angeles: "Once the body was left hanging, a young child ... wrapped their arms around the legs. 'Come down, daddy, come down,' they pleaded."

This incident was not an isolated event. Shortly after, white communities started mass deportations of Chinese people from various towns. In locations such as Tacoma, Seattle, Redding, Pasadena, and Eureka, groups of whites gathered in Chinatowns and forcibly removed inhabitants, firing upon those who tried to escape and setting ablaze their residences. Large sections of Chinese settlements across the Western region turned into charred remnants. Authorities rarely pursued legal action against the offenders.

In Washington, lawmakers were gearing up to make their move. In 1882, Senator John Franklin Miller of California, who had just taken office, presented Senate Bill 71. This proposed law carried significant weight as it aimed to prevent new Chinese workers from entering the country for two decades and stop courts from naturalizing Chinese inhabitants. Throughout the discussions, Miller advocated for what he termed "intelligent discrimination," starting specifically with the Chinese population. He argued, "They are not suited; they never have been and never will be fit for American citizenship." Following negotiations which shortened the restriction period to ten years, President Chester A. Arthur enacted this legislation excluding the Chinese. Thus, for the very first time, the United States barred individuals solely due to their racial background.

Being strangers in a new land is depicted as much more than just the tale of an immigrant community resigned to a miserable destiny. Luo skillfully places personal experiences front and center within his storyline, preventing 'Strangers in the Land' from turning merely into 19th-century political history. Through this approach, he gives a platform back to those overlooked individuals—men and women—who faced relentless challenges during their assimilation into a foreign nation. He portrays figures who persistently and courageously demanded that America live up to its foundational ideals. These characters bring life to the book, populating it with narratives of perseverance and arduous triumphs alongside poignant tales of grief, brutality, and inequality.

As they progress, Luo uncovers a crucial aspect of America: The validity of a country's democratic claims must be assessed based on how it cares for its most vulnerable citizens. Simultaneously critiquing past failures and honoring those who resisted, "Strangers in the Land" stands as an indispensable addition to the canon of American historical literature.

Makana Eyre is a journalist located in Paris. He wrote "Sing, Memory."

Strangers in the Land

Exclusion, Inclusion, and the Grand Tale of the Chinese in America

By Michael Luo.

Doubleday. 560 pp. $35

Post a Comment for "A New History Revives the Untold Stories of Chinese Immigration"

Post a Comment